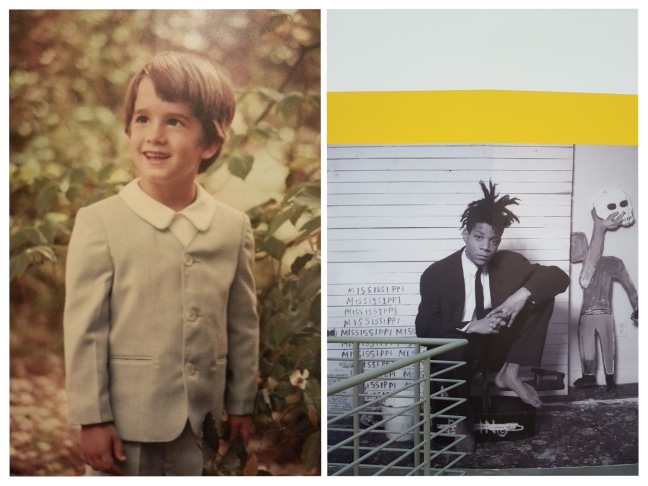

Above photos: That’s me on the left, during one of the formal photograph sessions I talk about not liking below. I remember touching that leaf with my left hand. It’s one of my only memories from my life before arthritis appeared. On the right is Jean-Michel Basquait. I saw this on the wall outside an exhibit on him at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. The lettering on the lower left popped out to me. Racism is a large theme in his work and this exhibit. Mississippi’s shadows seem to follow me no matter where I go, but so does its light.

Outside: Seeking a Savior for Liberation from the Bondage of an External Oppressor.

All of my life I could give two shits about Europe. So why did I travel here? I retained very little of my European history or literature classes. In fact, it was good fodder for sleep. Whatever I did remember, I labeled it as rubbish and intentionally forgot. Until recently, I existed in a very polarized world. Growing up in Jackson, Mississippi will do that to a person. Socially, things were often framed in the context of black and white. I mean this both in terms of black and white people, but also in terms of morality. Things were often right or wrong. The Church was omnipresent and potent in the air that raised me. My world was divided into good and evil based on subtle and not so subtle messaging. These polarities created a nice x&y axis for my early development. Black and White, Good and Evil.

However, I did a funny thing when filing things into these categories. I put “white,” “power” (and certainly all things “white power”), and white culture into the evil category and “black,” “soul,” and black culture into the good category. Sure it might sound preposterous and obviously flawed, but that was not my experience. Inside, this sorting process was subtle and subversive, occurring in the quietest of voices easily missed in the noise of modern life. It took me almost four decades to understand. Early on, I felt a great deal of shame for being white, because the people I saw in certain roles of history that looked like my parents and grandparents acted like the evil people in the fairy tales that I read. They also reminded me of the angry mob of Romans in the passion play of Jesus, which I heard every year when the liturgical calendar made its approach towards Easter (or 24/7 on the local access T.V. channels). I saw a clear similarity in the spirit of those yelling “Crucify him!” from the ancient Bible story and those spitting hatred at the Little Rock 9 or James Meredith, as they broke the barriers of public school segregation.

Closer to home, I saw the ripples of history in my daily life. Most directly and consistently, my family had a black maid named Marie. Maids were historically know as the “help,” and the economic structure is a direct descendant of the Jim Crow era and, ultimately, the plantation system. This complex and confusing dynamic was “Hollywoodized” in the popular novel and screenplay “The Help,” which takes place in Jackson about 15 years before I was born. I saw it at our country club, where the rich, white patrons were waited on by an almost exclusively poor, black staff in a setting that was uncomfortably plantation like. I saw it at church where the only black faces in the vicinity were custodians and homeless people on the sidewalk. I saw it in 1997, when as a summer camp counselor, I took a group of 10 black middle school students to see Jackson’s first black mayor get inaugurated, where we passed a white man holding a picket sign that read, “Nothing good ever happened when the monkeys took over the plantation house.” The list goes on…

I felt the tight and repressive social norms of the richest class every where. I saw it at church, at school, various country clubs other than the one we belonged to, at the Oil and Gas Club (private club on the top floor of a building in downtown Jackson for select members of the energy sector), at the Junior League of Jackson, and even at clothing stores buying nice clothes for church and family portraits. I have vivid memories of sitting at the Episcopal Cathedral on Sundays, silent and mostly still, dreaming of being across town in one of the gospel churches where it seemed ok to dance and shout out loud, shake a tambourine, and pass out as a result of being so moved by the Holy Spirit.

Historically, like the greater Deep South region, Mississippi was predominantly a mixture of western Europe and western Africa. The gulf between the extremes was and is stark. But, I was clear that I sided with the slaves, with those who sang the blues and who inspired Elvis Presley to sing and dance, with those who cleaned houses and served food, talked jive, and walked with a swagger-laden strut. I championed the ones I felt were, ironically, free and whose humanity matched the way I felt deep inside.

Now, it seems logical that I would go on the create a world where Europe was the source of evil, of oppression, of prophet killers, and an inhumane way of being that trickled down into the cultures and the people there within. This cultural plague had made its way to North America and to Jackson and into my house. In my own subtle and often silent way, I rejected it. I protested going to church and argued for the division of church and Jesus. I wore sweat pants in formal family portraits, argued with friends that Marie was not our maid, but our housekeeper and family member, and openly dissed the Confederate flag, debutante balls, hunting, and country music.

But instead of really fighting it at every turn, I repressed it, lived with large amounts of cognitive dissonance, and went with the flow of privilege. But I also identified myself with black folks and the parts of Mississippi that seemed to originate in west Africa, becoming biased towards them. I was never extreme in my approach. I never tried to overtly “act black” or openly “chant down Babylon,” but I did start to develop a belief that people like me and my community were the problem with the world. To sit with that belief and feeling was too much. I couldn’t reconcile that I had these oppressive energies in me and that I was a part of several western European lineages. It didn’t fit in my polarized framework. So I shelved it in the furthest recess of my mind where it could seep and fester for a few decades.

I slowly began making my way out of the south. First to college in Richmond, Virginia (yes, it was the capital of the confederacy, but very close to the Mason-Dixon Line:), where much of the campus community came from outside of the south. It was while I was in college that I was able to go to Africa as an exchange student. People often asked me why I chose to study there, while most of my peers chose European destinations. For me, it was my opportunity to learn about the other half of what I consider my native culture; the half that I was proud of and identified with in my soul. I felt it was important to experience being a racial minority, to flip the scenario and be the outlier. Even though there were several fallacies in my plan to “be a minority”, namely, the power dynamics I enjoyed in Ghana because of my skin color, my aim was true. The last reason I went, was to be more like my first hero (outside of my brother), Neil Peart. The legendary drummer took a trip to Africa to absorb the culture and the rhythms, penning a book called The Masked Rider. I think I was 9 when I learned about this, and I was in awe.

The experience was incredible. I’ve always said, “There was my life before Ghana and then there will be the rest of it.” I grouped my classes on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, so I was free to travel for most of the week. I took a full course load of mostly afro-centric classes and I had three drum teachers one from each of the major ethnic groups within Ghana. I felt very wild and very free from most of the rules, and pressures, and conveniences I knew. I also felt very close to the Earth. I remember thinking, “Is this what it feels like to be indigenous?” While those are comical statements in hindsight, I was taping into some essential qualities about what it means for me to be in right relationship to myself.

Outside of these romantic memories, I also came into contact with harsh realities left in the wake of colonization. Although rare, I felt hatred from black students the Pan-African student group, Africans and African-Americans alike. I visited Elmina Castle, where the slaves were put onto ships headed to the middle passage. Near the castle, I was asked for money by a young girl, who referred to me as “sire,” a staggering relic from the days of active trading. I received another sick artifact of the past from a Ghanaian evangelical, who warned to repent soon, or suffer the same fate as the poor African nations for not accepting Christ earlier in history. My blood boiled, hearing this, and I wanted to destroy whichever sect of missionaries I felt sure introduced such a logic driven by blame and shame.

It was also the first time I could clearly see the division and separation between West Africans and African-Americans. I remember being at the airport to pick up my parents. At the same time, dozens of African-American businessmen were arriving for a conference designed to spawn better business ties between Ghanaian and African-American owned businesses. I was stunned by the difference in skin tone and bone structure as a result of over 250 years in the US, mixing with a larger gene pool. All of these experiences gave me a completely new dose of colorful information to add to the polarized, biased, and bigoted experiences of growing up white in Mississippi in the 1980’s and 90’s. Ultimately, I became more overwhelmed by the power and gravity of history and my place in it.

Inside: Seeking a Savior for Liberation from the Bondage of an Internal Oppressor.

While much of my time in Ghana was spent exploring and learning about my outer world, my inner world was undergoing an equal amount of change. The theme of oppression and freedom from bondage carried over into my body. I was diagnosed with Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis during the summer between 1st and 2nd grade. It happened over night. I literally woke up one morning, went down stairs as usual and the first thing out of my mother’s mouth was, “What’s wrong with your knee?” The next thing I remember was being in the emergency room, feeling a bit like ET when he and Elliot were quarantined in the house, overrun by scientists in scary sanitation suits. And so began my life living with chronic illness and pain. Between the ages of 8-15, the “dis-ease” was severe and I was noticeably hobbled. In hindsight, I was tethered to pain. Concurrently, I began to experience a spike in my already high levels of anxiety. I was a positive and upbeat kid, who didn’t want others to worry. But inside, I was internalizing some pretty severe messages, namely that I was broken, I was alone in my pain, and no God would or could save me.

It is no wonder that the first time I got high in Ghana, I got hooked. It was such a beautiful scene: I was on the roof of my dorm building with a group of international and local students watching the sun set. I remember starting to feel the THC set in and a rush of anxiety followed. This was not the first time I tried smoking pot. I gave it a whirl a few times in highschool and had a terrible time. It was similar to the classic scene from the stoner flick, Friday. No angel dust needed, I had my own giant sized, amped up anxiety. I ran up and down the street trying to sweat it out, as onlookers laughed hysterically. So almost five years later, when I tried it again in Ghana, and managed to push through the anxiety, I thought I was cured. I found myself in a paradise free from the background noise of pain and anxiety. I felt a new level of relief and serenity. In that moment, I felt free from the bondage of an oppressive inner world, both physical and emotional. Marijuana became my Messiah, Lord, Savior, and Higher Power; something outside of myself that set me free.

Maybe that’s why I always felt drawn to the West African elements in Jackson? I felt deeply connected to what I saw as a community of people in pain, shackled and bound by oppressive forces larger than themselves, struggling to be free. I also perceived a certain quality of aliveness in their day-to-day expression (walk and talk) and in their art spanning generations.

So I returned home from Ghana an altered young man. I had touched a part of myself that felt wild and free, more in touch with a way of life that was closer to nature’s rhythms, and free of the pressures of “civilized” society. I also had a new tool in the form of marijuana, that could alter my perception and clear my pain and worries for a little while. In that spirit, I returned to Virginia to finish college and join a rock band of brothers. We headed west for Portland, Oregon to join the migration of indy rockers chasing their destiny in the city of rain, roses, weed, and white people. Statistically, Portland is the whitest major city in the US. I’m not sure how the numbers stack up in terms of rain, roses, and weed…but I know they are “high” on all accounts.

Over the next 14 years, I made a lot of music and was able to live into a side of myself that was a bit wilder than anything before, but hardly free. I became dependant on getting high to feel normal or relaxed. I relied more and more on marijuana to access a source of freedom, relief, and even salvation. At the time I thought it helped me access my true identity. In reality, it was making me more and more isolated, depressed, and distant. It affected how I showed up in all aspects of my life. Worst of all was the level of shame that it added to my internal world. That was the last place I needed more of anything. And thus was my uniquely, uncommon ride into the cycle of addiction.

As I mentioned in my last post, the life I was creating eventually exploded (see previous post “Donde Diablos Estoy y Como He llegado Aqui?“). I am beyond grateful to be at this pont in the healing process. I have worked hard and swam out past many breakers and break downs to get to the place I am currently. This place is much more calm and quiet and free, and I’m clearer about who I am and what fills me with passion. (I will absolutely fill in the details about the healing journey over the last several years and how it delivered so many mentors to me through graduate school, a longterm men’s group, multiple spiritual paths, Process Work, and the renewed love of music and drumming.)

Two final elements remain to fully answer the question of, “Why am I in Europe?” Last winter, I met two specific individuals during my time in the winter intensive training at the Process Work Institute. The first was an Italian man, named Giovanni Fusetti. He is an internationally renown trainer in the art of clowning. I kid you not. He is also an absolutely phenomenal man who has loads of knowledge and energy. We talked a lot about myth, power, men and masculinity, and European history. He talked about a time when Western European cultures still lived off of the land, akin to the indigenous people of the world. Also, he was able to uniquely frame much of the back story about the centuries of war and abuse within Europe that gave rise to the colonies in the US, largely by monarchies and the Church. I could see that before the US colonists were abusers, many were abused and indentured themselves. For the first time, I was able to view Europe and Europeans (and their descendants, like me) with a little empathy and compassion and I wanted to learn more about the “preface” to our story in the U.S first hand.

The second was an African-American woman I met briefly during a weekend workshop on “Race, Gender, and Economics.” During the workshop, she emphasised the difference between genotype and phenotype, as a reminder that one needs to look way beyond skin color, to understand someone’s genetic complexity, much less identity. This alone, completely begins to dismantle the institution of racism.

We didn’t talk until the end of the workshop. Our meeting was brief, but her impact still lingers and drives me eight months later. She heard my last name and asked if I had Scottish ancestry. I cautiously replied, “Yes” and beaming with pride, she said, “Me too!” She proceeded to tell me all about the tartan and the crest of the clan she comes from, and how she is a regular at local Scottish heritage festivals, dressing in full Scottish regalia. I was dumb founded, struggling for words as this black woman was owning her European ancestry with total pride. My mind was blow, and my heart was melting. Something in that moment allowed me to be proud of that part of myself long covered in shame. Right or wrong, the “something in that moment” is that she was black. Just like the time it took a black person to open me up to country music or the Kappa Alpha Order. Now it was my Scottish ancestry. What an incredible world…anything but black and white.

And so, for these reasons I am in Europe at this moment in my life. With beginner’s eyes, a mind blown away, and a heart broken open by this world, I bought a one way ticket, held my intentions clear, and boarded a plane.